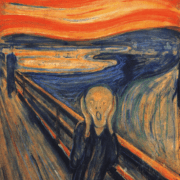

The sum of all our fears

by John Kananghinis

Fear is the ultimate weapon of the autocrat.

Be it fear of manufactured external foes, fear of others due to ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or any number of other differentiators, fear of the state security apparatus or fear of an unseen enemy – from a supernatural force to a plague.

Throughout history all have been used to control a cowering populace. In fact most have been used in the last 100 years. In each case the results have been horrific. Hitler’s Holocaust, Stalin’s purges, Mao’s Cultural Revolution, Pol Pot’s killing fields, the Rwandan genocide, the Balkan wars, Argentina’s disappeared; all used fear, in some form, to motivate and justify atrocities.

One would think that such examples would have taught us to be wary and sceptical of fear wielded as a rationale for state action, particularly action that is externally aggressive or internally regressive of freedoms, or both.

Yet fear itself remains the most pernicious enemy.

Famously, Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, in his 1933 inaugural address “…the only thing we have to fear is fear itself— nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyses needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” He was talking about the great depression. The thought is clearly applicable to our current predicament.

In today’s world we have combined three otherwise relatively minor fears into an all pervasive mega social fear. They are the fear of giving offence, the fear of disapproval and the fear of ostracism by the mob. Social media now crushes critical thinking, open and frank (yet respectful) debate, inconvenient truths and acknowledgment of failure. For lives lived online there is no greater fear than being ‘cancelled’. Being shunned and excommunicated by the online mob, who, as with all mobs, move further from rationality as they increase in size.

Such fear is combined with a culture of increasing selfishness and entitlement, bordering and regularly straying over the line into narcissism. A culture that prioritises feelings over facts. The result is that feelings of fear can lead to irrational decisions, or, worse still, be easily manipulated.

In such an ego-centric climate, and with the demise of religious belief, the greatest fear of all is driving our reactions to perceived existential threat. The fear of death.

It is tritely said that death is part of life. Yet, with our increasing belief that we have mastered nature, western developed societies have become so averse to and afraid of death that each departure is treated as a tragedy, irrespective of age and circumstance. That is not to be unfeeling but simply to acknowledge that, try as we might, we cannot outrun death.

If we struggle to accept that fact we will regularly find ourselves making decisions based on denial of fact and mortal fear. Ironically, decisions we may live to regret. In the words of philosopher and Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, “ It is not death that man should fear, but he should fear never beginning to live.”

Of course, responses to challenges such as the current pandemic need to be timely, founded on expert advice and proportionate. Some governments have failed on some or all fronts, with devastating human cost, others have scrambled and barely kept up, a few have achieved relative success, while some may have overreacted – only time will tell. Naturally, it is better to err on the side of caution, but there is a vast difference between caution and fear driven panic.

More concerning is that, in a climate of fear of social censure, critical analysis and legitimate debate have been silenced. Either by weight of the mob or by cowardice. After all, in our society, politicians are allegedly servants, not masters, of the people and they must be subject to scrutiny.

In a democracy we should not fear censure for asking pertinent and searching questions or for seeking rational and reasoned explanation of government action, especially if we are to surrender our freedoms for the greater good. Of course there will be occasion when exactly such surrender is required, and all should play their part. That is part of the bargain of living in a civilised and caring society. However, any restriction of freedom must be as little and as short as possible. If not, more harm than good is the likely outcome.

If we are to preserve our freedoms (and it is easy to forget how hard won they are) it must be reason that guides our actions, not fear of political disadvantage, fear of disapproval, fear of hurt feelings or even fear of death. To give in to such fears can lead us down a path to the one thing we should truly fear, the death of our democracy.