Helping your organisation develop a values based culture, how Bushido shows the way

Open a paper, turn on a TV, or click something that’s not bait and you will not have to turn far, wait long, or search hard to find a story about bad corporate behaviour. This is no better illustrated than by the recent Mossack Fonseca (Panama Papers) and Unaoil revelations (ably supported by a cast of local stories such as 7/Eleven, CommInsure, Wilson Security et al).

So, is the surfacing of these revelations a deterioration in corporate culture and associated decline in ethical standards, or has this always been the way in which the spinning of the globe has been oiled and there has just been a rise in investigative reporting that has brought these issues out into the open?

The answer is likely a mix of the two, however the naïve optimist in me would like to think that a fall in the standard of behaviour accounts for the majority of the stories that have been broken; as opposed to the alternative of low-standards having always existed out of view.

Progressing on that basis, the question arises how do organisations ensure that their much vaunted corporate values are adhered to in the pursuit of shareholder value and returns? As we know, dollars (or perhaps what they represent) are very powerful things.

Societal values are evolutionary in nature; by way of example I cite our acceptance of violence. It wasn’t so long ago that a punch up at the pub, though not encouraged, was accepted as a form of dispute resolution. Rightly, this is no longer the case.

I therefore contend that organisations (be they government, corporate, or not-for-profit) need to have an adaptive system in place that educates their operational headcount about what is, and is not behaviourally acceptable. A one-off, tick box exercise to satisfy a checklist would not be sufficient given that the subject matter is undergoing continual metamorphoses.

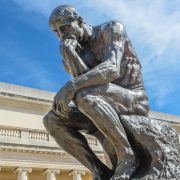

An enlightening parallel can be found in Bushido: The Soul of Japan, an explanation, if you will, written by Inazo Nitobe[1] of the moral principles that Samurai were required or instructed to observe.

The nature of the system was such that it was not a written code; rather it was a set of principles that were handed down organically (not unlike an oral history) either via word of mouth, or more impressively through deed.

Interestingly, the paid fighter was naturally recruited from some fairly rough and ready personnel, it was through the generational application of the ‘unwritten moral code’ that Samurai came to be highly respected and seen as both the exemplars and guardians of the highest behavioural standards.

It was a sorting of the wheat and chaff that conveyed enormous privilege and responsibility upon those within its ranks.

It is possible to make the argument that our leaders are those now charged with passing down through word and deed the standards that are expected of their charges. These standards must be the living representation of ‘Value Statements’ and take into account the evolving expectations of society at large.

As outlined by my colleagues Rob Masters (Contrite Contrition) and John Kananghinis (The Values Deficit) in this edition of Words and Insights society at large has had enough of hearing mealy mouthed platitudes laid at the foot of the most recent scandal. They want to see leaders who own the situation and the moment; leaders who embody their values statements through their actions; thereby laying the foundations and paving the way for the next generation of Samurai to follow them, and protect society’s behavioural standards.

For a brief history of Japan, click here

[1] Inazo Nitobe (1862-1933) was born in Morioka, Iwate prefecture. After graduating from Sapporo Agricultural School, he went to the United States and Germany, where he studied agriculture and economics. On his return to Japan, he held various positions in education. From 1920 to 1926 he stayed in Geneva as Under-Secretary General of the League of Nations. After retiring from that post, he dedicated his life to peace. In 1933 he died in Banff, Canada.